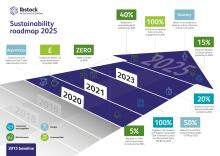

What happens to this waste? The surprising answer is some of it ends up making cement. The cement industry is working hard to decarbonise, and a big part is fuel switching from fossil fuels (mainly coal, due to the very high temperatures needed) to renewable or zero-emission sources. Fuel switching is the second biggest element in our roadmap to beyond net zero after Carbon Capture, Usage or Storage (CCUS), contributing 16 per cent of the reduction needed. Cement will still need to use CCUS because of ‘process emissions’ from the chemical breakdown of the limestone, but we can switch out emissions from the fuel burned.

There are a range of fuels that are suitable for use in cement – MPA’s members use tyres, sewage pellets, waste solvents from industry, and refuse-derived fuel (including paper, plastic and textiles that can’t otherwise be recycled). We have also trialled hydrogen and plasma (a form of electrical energy) in a project funded by BEIS. A mix of hydrogen, MBM and glycerine (a by-product of making biodiesel) was used in a world-first commercial-scale trial of a net zero fuel mix for a cement kiln. It is important to stress we are only talking about waste biomass that has gone through a first use.

The challenge for our industry is making sure we can access waste biomass. In recent years there has been a very slow rise in use (just one per cent overall in 10 years) and a decline in the use of 100 per cent waste biomass fuels from 6.5 per cent to 3.6 per cent of thermal input. This is because the fuels are being incentivised out of the sector.

The challenge for government should be to set policy to make sure the best use is made of waste that can’t be recycled but can be used for fuel to displace fossil sources. The Green Gas Support Scheme, the successor to the Renewable Heat Incentive, was intended to support the use of waste material to generate biomethane for injection into the gas grid. Its effect has been to divert this waste material away from industrial use.

A report by Eunomia for MPA (available on request) found that using food waste in cement manufacture had a greater climate benefit than alternative treatments – each tonne of food waste being used avoiding nearly half a tonne of carbon dioxide, more than for the same waste being used in anaerobic digestion for biomethane or in energy from waste plants to produce electricity. The Green Gas Support Scheme, which subsidises anaerobic digestion at £29/tonne of food waste, delivered a carbon emissions saving of around 3kg/£, whereas if the equivalent support was offered to cement producers, the saving would be nearly 8kg/£.

Waste biomass is a finite resource that has a significant potential for tackling climate change, but we need to be using it to its fullest potential. Using waste biomass in the manufacture of cement brings greater value for money and significant emissions reductions compared to other uses. With the Biomass Strategy expected in 2023, now is the time to recognise the importance of waste biomass for industry and get the best out of our Christmas dinner leftovers.

Thanks to Robert McIlveen, Director of Public Affairs, Mineral Products Association, for the above piece, which first appeared on the PoliticsHome website.