Very big numbers can be the best way of putting a very big issue into a relatable context, as Dr Pascal Peduzzi demonstrates at the start of our conversation.

“We use 50 billion tonnes of sand and gravel every year, enough to build a wall 27 metres wide and 27 metres high around the equator. So, we have a lot, but we are using a huge amount. In some places, we are running out of these resources,” says Peduzzi.

“We issued alerts on the environmental impacts related to sand extraction, but this question was overlooked prior to the GRID-Geneva reports. Now we have two UNEA (United Nations Environment Assembly) resolutions and one motion from the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) on marine sand. This has brought the issue of sand into the political agenda. We also highlighted where the extraction of sand will have the highest impacts in the future, such as in Africa.”

GRID-Geneva is the UNEP centre for analytics. Created in 1985 to help transform data into information to support environmental governance and policies, it uses statistics, satellite imagery, in-situ and GIS models and produces scientific information to assess current environmental status, identify past trends or predict future status based on modelling.

“Since 2014, GRID-Geneva has been working on the issue of sand and sustainability and was one of the pioneer institutions to alert governments regarding this looming sand crisis. It was an issue that had, until then, been totally overlooked,” explains Peduzzi, who was one of the selected authors for the 2012 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Extreme Events. “In 2019 and 2022, we issued reports with recommendations to governments and other stakeholders. At the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in 2022, all 193 countries present gave GRID-Geneva the mandate to strengthen the scientific, technical and policy knowledge with regard to sand.

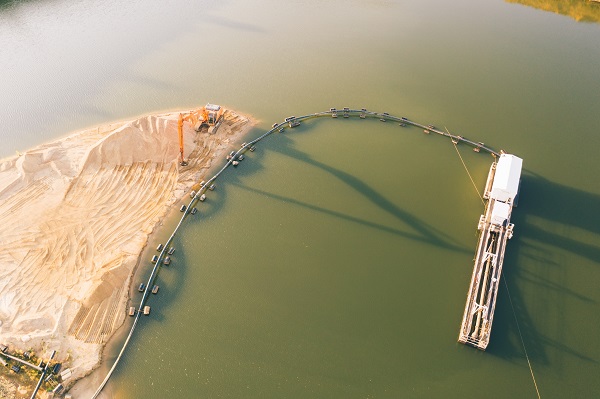

“We have developed a technology using artificial intelligence (AI) to monitor sand extraction in the marine area worldwide. Monitoring the extraction of terrestrial and riverine sand is not easy. We plan to create a Global Sand Observatory based on a wide network of partners and are currently raising funds for it. This network, and we already have 40 interested partners, will be monitoring sand use and sand extractive impacts, issuing recommendations on standards and policies, as well as gathering technical solutions.”

I ask Peduzzi, who holds a PhD and an MSc in Environmental Sciences, with a specialisation in GIS (geographic information system), what impact the GRID-Geneva team’s April 2022 published report Sand and Sustainability: 10 strategic recommendations to avert a crisis has had on influencing key global decision-makers.

“It was circulated to UNEA-5 and led to the adoption of resolution 12 on Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management. The media coverage was very high: more than 400 articles were in the main media in the week following the launch. It did shed light on this issue which was so far overlooked, yet a lot of things remain to be done to influence the global decision-makers. It will take more than a report.”

Peduzzi says the April 2022 released report made clear that sand must be recognised as a strategic resource, not only as a material for construction but also for its multiple roles in the environment. The GRID-Geneva team emphasise that governments, industries and consumers should price in sand in a way that recognises its true social and environmental value.

“Current practices do not include the real costs of sand. Sand is producing services which have a value, and this value has been dismissed,” Peduzzi explains. “If you extract sand from dynamic settings like the beach, rivers, lakes, and marine areas, you are affecting water supply, shoreline protection, biodiversity, fisheries and other livelihoods such as the collection of crabs. You are inducing land degradation, and erosion, affecting the river banks as well as coastal areas. All of these impacts have a cost. So far, this is pushed on others; something economists call ‘externalities’. Now we can adopt new standards which will reduce such environmental impacts and related costs.

“If higher standards are being accepted regarding sand extraction, this may be more costly to extract. Same if you need to provide funds for restoration after exploitation.

“The new price will need to integrate such additional costs. For the final users, this may only add a small percentage to the cost of the infrastructure.”

Peduzzi argues that while the price per tonne of sand will be higher, this doesn’t mean that this would be a loss for the company as if the standards are accepted internationally, it would leverage the playing field and would benefit companies which are already well advanced in their extractive practices. “It is a matter of limiting the externalities of costs on social, environmental and other economic sectors,” he stresses.

UNEP’s April 2022 Sand and Sustainability report also recommends an ‘international standard’ on how sand is extracted from the marine environment – and the banning of beach sand extraction. I ask Peduzzi who would set this international standard and introduce the beach sand extraction ban, how both would be policed, and whether penalties for breaches be enforced through fines or court action leading to possible prison sentences.

“Extraction of sand in dynamic settings, especially with regard to beaches, is leading to significant impacts. Not only the obvious coastal erosion and the fact that this would prevent future touristic and recreational use of the beach, but the salinisation of coastal aquifers, the reduction of protection against storm surge, which will already be intensified with Climate Change and sea level rise.

“This is why it is important for countries to ban beach sand mining and to make this enforced via usual law enforcement ways for any law-breaking. This needs, however, to be done with support for the transition of the workers who shouldn’t lose their livelihood. This is why we need to invest in infrastructures and tools for extracting sand from quarries.”

Does Peduzzi believe a circular economy for sand is achievable? “Achieving circularity, given the dependency we have on sand and gravel, will not be easy. However, there are ways we can significantly improve the industry by adopting several practices. We can reduce the demand for sand and products derived from sand; replace naturally occurring sand with alternative materials; reuse sand and products made of sand at the highest value possible; and recycle sand and products made of sand that cannot be reused.

“We also need to rethink the way we are doing our development, transferring public mobility emphasis to metros and trains rather than individual cars. This would reduce the need for new roads and related sands. The new tunnels built for the metros can provide building materials, thus freeing up building materials to use elsewhere. This will also take up less of the earth’s surface area and transport people at a higher speed as metros and trains are not stuck in traffic jams like cars, which are, anyway, parked 98% of the time. It would also reduce the need for car batteries. Combined, these are important steps in making the entire value chain more sustainable.”

I highlight to Peduzzi that across the world’s quarry and wider building materials supply businesses, there has been a big increase in recent years in the amount of manufactured sand being produced for use as a construction material. Does he think this represents a long-term alternative in terms of quality and sustainability to natural sand extraction?

“Despite the increase in energy, manufactured sand usually has less impact than extracting sand in dynamic settings such as rivers, beaches or marine environments.

“There is a resource which is similar to manufactured sand is what we call ore-sand, i.e. the co-generation of sand from the mining of other ore, such as iron.”

I am curious to know what Peduzzi thinks would happen to the world’s sand resources if the work of UNEP/GRID-Geneva and other sustainable environmental campaigners ceased.

“This looming sand crisis is coming. UNEP is alerting on this issue; this needs to be addressed by countries and by the economic sectors involved. The issue will only become more acute. We are trying to wake up various sectors on this. If we fail and no other institution succeeds in changing the practices, this sand crisis will get worse, and we will repeat what we have done for climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, i.e. only reacting instead of preventing a crisis.”

Peduzzi outlines various reasons why he thinks very little attention has been historically given by politicians and the general public to sand sustainability.

“Governments have many issues to deal with - security, economy, development, climate and other environmental issues. Sand is only a new flashing red light on their board. Secondly, we have the impression that sand is a common material and that we have plenty of it. However, our use has tripled in the last two decades. The amount we use is very large. And we are fully dependent on this material for all our infrastructures: roads, buildings, houses, schools, hospitals, dams as well as coastal protection, or industrial sand for glass or even computer chips. If our entire development depends on sand, it cannot be a common material but a strategic material. This requires a change of perception, but this takes time.”

Asked what he finds most satisfying about his work, Peduzzi, a Swiss national who lives and works in his home city of Geneva and who also works as a part-time teaching professor at the University of Geneva, says it means a great deal to him and his team that GRID-Geneva and UNEP at large are supporting global good by improving people’s relationship with the environment while trying to facilitate the transition toward a more sustainable future. “I meet great people who are very keen to improve our sustainability practices,” he adds.

And what does he see as the biggest challenges he and his colleagues face? “Humanity has never faced such large challenges. The triple planetary crisis - climate, biodiversity and pollution - is posing many challenges. My team and I are working with many other actors, but the task is huge. We are struggling with the inertia of the system. The too little, too slow, too late decisions and actions toward sustainability. Most people are not aware of the urgency posed by the triple planetary crisis. We need more political will, more long-term vision for the economy and more resources allocated to dealing with these issues.”

I ask Peduzzi how he thinks UNEP/GRID-Geneva’s work would be deemed a success. Are there specific targets he and his colleagues are working toward? “We need to work step by step, and UNEP cannot do this alone,” he stresses. “Sand is the biggest solid material extracted by humans; this issue will not be resolved easily. It will take more than a decade to improve the situation.

“We already had the success that in 2019, for the first time, sand was recognised as an issue by 193 governments. In 2022, we received an official mandate from those governments.

“If we succeed in creating the Global Sand Observatory, this will give us more weight to promote this issue and related solutions.

“Then, working through time, the adoption of new standards would be a great achievement.

“But clearly, the question is not about success for GRID-Geneva; it is about achieving sustainability.

“The question of sand is only one more issue. Climate, deforestation, biodiversity loss, overfishing, all these issues are telling us that we cannot continue to exploit the earth in a linear way: extract - transform - use and dump material. Something that is sustainable is something that can last. Non-sustainable development will collapse. Sustainability is not a luxury for enlightened ecologists; it is the difference between living in harmony with nature or a collapse of our ecosystems. We are walking toward a cliff and about to make a great step forward. It is urgent to change the direction of our development and move toward sustainability. This will require completely changing how we produce and consume goods and services. But it will greatly improve our quality of life.”