With EU Stage IIIB emissions regulations getting ever closer, engine makers now have clear ideas of how they intend to meet forthcoming legislation. Geoff Ashcroft reports on what this means for operators

As engine manufacturers reveal just how they are going to tackle the latest emissions legislation due to come into effect next year, customers should be prepared to face up to higher servicing costs as a result of adopting the very latest engine technology as part of their new machine purchases.

Europe's Stage IIIB emissions regulations that come into effect for engines producing 130-560kW from January 2011 stipulate that Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) levels must be reduced by 45% and Particulate Matter (PM) must be reduced by 90%, when compared to current Stage IIIA requirements. These reductions drive the need for exhaust after-treatment to deal with particulate matter, but will also require enhanced engine technologies that could involve combinations of optimised combustion processes through the use of high-pressure common rail fuel injection, multiple variable geometry turbochargers and cooled exhaust gas recirculation to deal with NOx.

The same standards will eventually apply to lower powered engines producing 56-129kW, although the introduction of Stage IIIB legislation governing this power sector doesn't come into force until January 2012.

And it's only going to get tougher as engine makers head for ever-cleaner Stage IV emissions levels, due to come into effect from January 2014.

Currently, there are currently two distinct routes that most engine makers are taking towards cleaner emissions. One route involves

The alternative to SCR is to employ a combination of Diesel Oxidation Catalyst (DOC) and Diesel Particulate Filter (DPF) and this is favoured on engines that currently use EGR (exhaust gas recirculation) techniques. Diesel Oxidation Catalysts consist of a catalytic coating on a honeycomb substrate for oxidising particulate matter. It operates in a passive-only mode without active regeneration, so is less efficient at particulate matter reduction than the DPF.

A DPF captures particulate matter in a porous medium as the particles flow through the exhaust system. This system operates in both passive and active regeneration mode to oxidise the particulate matter and extend its service life.

Neither system offers fit-and-forget technologies and both bring additional servicing and running costs to machine operators.

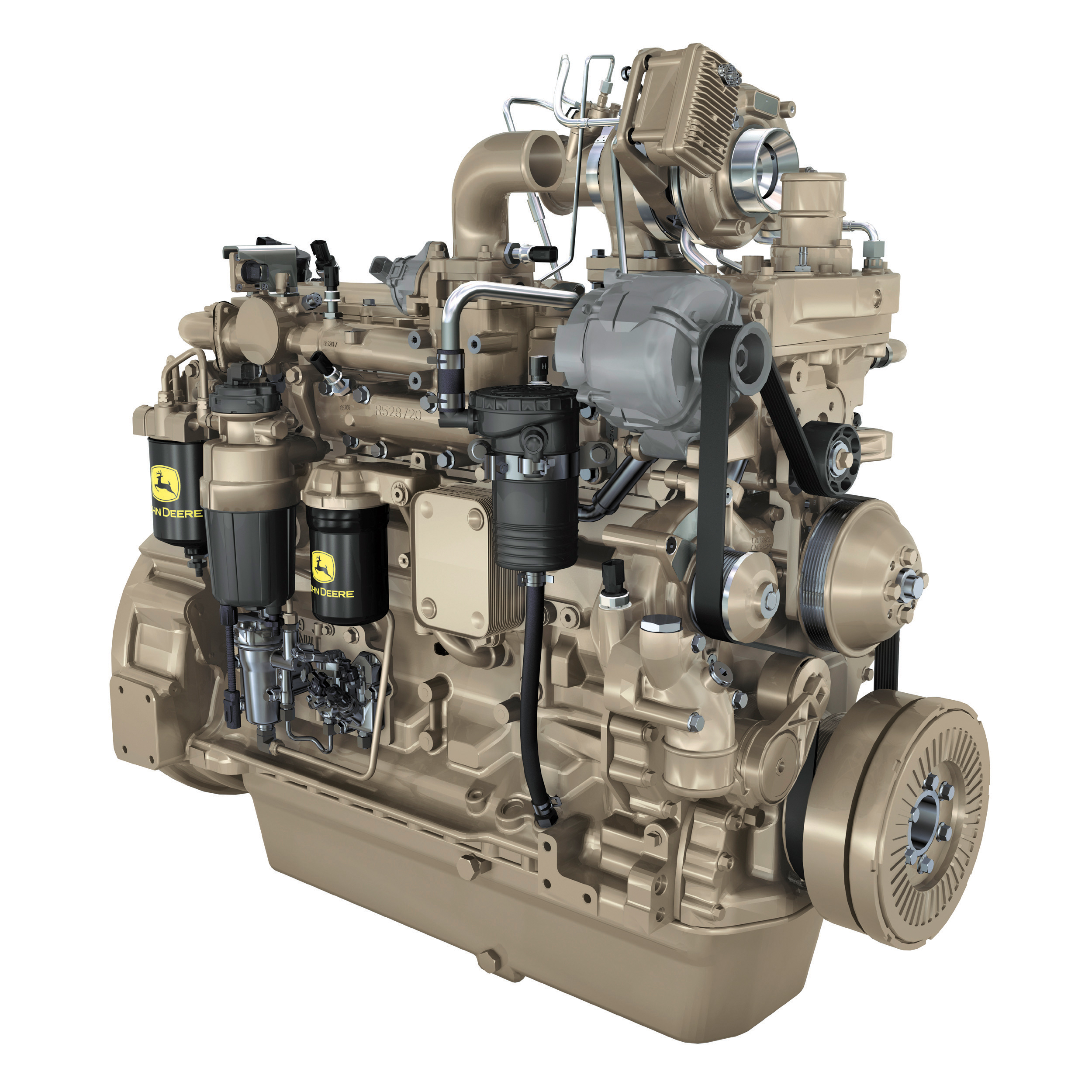

Deere Power Systems is favouring the DOC/DPF route, which it is employing in combination with its exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) system currently used with PowerTech engines. The next stage sees the flagship PSX versions get twin-turbocharging to increase power density in a range that covers 168-448kW.

According to Scania, SCR fits the demands from customers in this segment with rapid response time and high torque at low rpm. The firm adds that only small modifications will be required for engines using SCR to meet the next phase of emissions legislation - Stage IV - due in 2014.

Called Bosch Emission Systems, the new company will pool its collective expertise to develop a modular solution that can be tailored to individual engine and application requirements using electronic controls and optimized burner technology for the regeneration of diesel particulate filters if required.

Bosch Emission Systems has said its solutions will be tailored to mobile and static plant, including construction machinery, commercial vehicles and agricultural equipment.

However, despite most engine makers claiming useful reductions in fuel consumption, which will no doubt be welcomed by operators, achieving such clean exhaust emissions will come with strings attached.

For many end-users, the addition of any exhaust after-treatment know-how brings with it a degree of add-on cost, which is expected to have a knock-on effect with machinery buying decisions.

Those with pending machinery fleet replacement plans might be tempted to bring forward their buying policies to benefit from the lower running costs of using plant and equipment with existing emissions technology.

"

"But there is much more of an immediate challenge for us working with OEMs to ensure that power train packaging and cooling requirements are met. Installation space is very tight in many items of plant and machinery." That cooling requirement can also be impeded by the use of engines running cooled exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) systems, which is a progression of early EGR systems.

Cooled EGR takes a measured quantity of exhaust gas and then passes it through a cooler before mixing it with incoming air as it returns to the cylinder to be burnt again. Exhaust gas temperatures in EGR engines, therefore, are reduced by engine coolant. But this raises the cooling system requirement and often dictates that upgraded fans and/or radiator capacities are required to deal with the extra heat generated.

But the trade-off means the 1200-series engines will demand either a bigger cooling package or more efficient fans, depending on the installation. And the firm has been working closely with equipment manufacturers to ensure these latest power units can be installed into existing vehicle frames.

In contrast, engine makers such as

And while this system places no additional demand on the engine's cooling system, it does require specific dosing equipment and an additional 'fuel' tank, into which the liquid urea is stored on the machine.

While dosing will be regulated through the engine's electronic control unit, the system will require operators to refuel both the diesel tank and the urea tank. And a vastly reduced power output is likely to be the result of letting the urea tank run dry.

Such a system will also require bulk urea storage too, according to the number of machines on site using an SCR-equipped engine. Though it is said to be much less susceptible to fluctuations in fuel quality when compared to DOC/DPF-based systems where substances such as sulphur can reduce the effectiveness of the treatment.

And with this in mind, Cummins believes that diesel fuel quality will be a critical part of meeting the 2011 emissions requirements.

"Ultra-low sulphur diesel (ULSD) will be necessary for most after treatment processes simply because high levels of sulphur will dramatically reduce the effectiveness of the exhaust after-treatment," added Nendick. "And a high rate of sulphates may result in an engine failing to maintain emissions compliance." While ULSD is available for on-highway use, its introduction for off-highway fuel is lagging some way behind. Since 2008, the maximum sulphur content allowable has been 1000 parts per million, which is being reduced to 10ppm in Europe by January 2011 - the same date that IIIB engines are required.