The UK building materials industry is having to cope with significantly rising production costs linked, among other factors, to the huge hike in energy prices and the construction and quarrying industries' loss of the red diesel rebate. The industry is also continually investing in new technology to help meet customer product demand while channelling further resources into recruiting and training its next generation of professional employees. But if you suggest to Dr Miles Watkins that UK building materials companies may need to lower some of their ambitious sustainability goals to enable them to maintain any sort of profit margin and growth in a tough trading environment, you get a cogent response.

"We have the physical world; on top of that, we have the social world, and at the top, there is the economic world. As far as the bit of the bottom is concerned, it is all over [for climate change deniers]. It will only get more expensive to do something," stresses Watkins, a former Aggregate Industries director of sustainable construction and former non-executive president and chairman of the Institute of Quarrying (IQ). "Either you understand this and have a business that can cope with the rise of investor and social interest in sustainability, or you are a business that can't be bothered, that gets a bit further down the road and sees its assets scooped up and bought by more savvy others."

Watkins, who has a PhD in Stakeholder Management from the University of Bath, stresses that sustainability is a big as well as hot topic within the UK building materials industry. He has been keen to focus on two areas he thinks can deliver the most enduring gains.

"I am particularly interested in [building materials] circularity and low carbon solutions, and the union of commercial activity and sustainability. I often see companies go piling off down a sustainability route almost in a vacuum, but it makes good sense to have a sharp focus on what makes their customers happy.

"I have always networked well in the industry through my work with the IQ and am broadly known for my work on sustainability, so most of the time, companies come to me for advice and support. What is good is that companies seek me out when their senior management is genuinely interested in doing something to improve their sustainability."

Watkins, who is based in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, central England, says he works with a range of quarrying space firms, including Breedon, John Wainwright & Co in Somerset, and, on the contracting side, with Associated Asphalt Contracting Limited in southeast England. Many of his client companies include some of his former Aggregate Industries colleagues. Watkins is also still working closely with the IQ on its approach to sustainable construction and the enduring performance of minerals.

"Some of the sustainability stuff does not get dealt with as businesses do not feel confident enough to give things a go. As such, a lot of the work I do with them is making sure their people feel they can make suggestions, ask questions, and bring things they read about into the workplace. It's creating an internal landscape where people feel confident to fully explore issues around sustainability.

"There is a real gap in the market when it comes to training in this space, including educating businesses about the trade-offs that need to be handled. It is very difficult to tick every box. Sometimes you need to untick one to tick another."

Aligned with his industry sustainability consultancy work, Watkins explains that he is in the process of building up two businesses.

"One is around polymers and waste plastic products. Abolishing all plastics would be crazy; they are an incredibly handy material. My waste plastic recycling interest came from a quarrying environment when I started thinking, 'What happens to all the discarded fluorescent vests?' My other business is connected to my work at Xeroc, which is championing Blue Planet Systems' carbon capture and aggregate upcycling technology. We have a licence to look at incorporating small-scale Blue Planet Systems' aggregates production plants into existing building materials producers' sites, using their waste as our source materials."

U.S.-based Blue Planet Systems' patented mineralisation technology is said by the company to be the only known scalable method for capturing and permanently sequestering billions of tonnes of CO₂. The firm says it can process, dilute and use CO₂ from any source, combine it with concrete waste at any concentration, and turn it into valuable building materials to enable carbon capture at a profit. Each tonne of its CO₂-sequestered aggregate is said to permanently mineralise 440kg of CO₂, preventing it from ever leaking or accumulating in the atmosphere. "What I really like is that it's quite practical technology that uses fairly well-understood science," emphasises Watkins. "In effect, it washes the aggregates out of the concrete." Blue Planet Systems' investor partners include Holcim, Mitsubishi Corporation, Calpine, Knife River, and KDC.

I was keen to speak to Watkins after listening to his fascinating and illuminating presentation at the British Aggregates Association (BAA) annual conference at The Palace Hotel in Buxton, Derbyshire, England, the day before the start of the hugely successful Hillhead 2022 quarrying, construction, and recycling industries' exhibition. During the presentation, he spoke of the need for building materials suppliers to maintain their admirable work to reduce their carbon emissions.

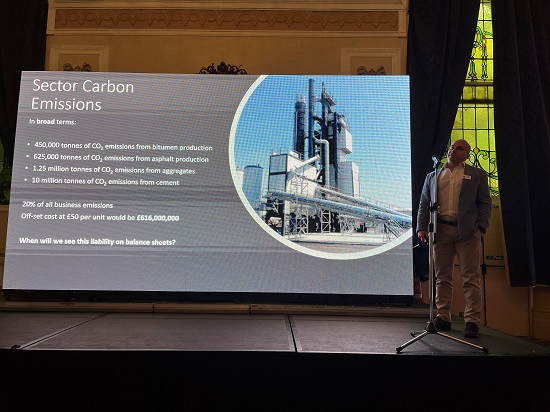

Highlighting the UK building materials sector's 'broad terms' carbon emissions to conference attendees, Watkins noted that bitumen production generates 450,000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions; a further 625,000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions come from making asphalt; 1.25 million tonnes of CO₂ is emitted during aggregates production; and a whopping 10 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions are generated in cement making. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given such figures, Watkins noted that the building materials sector is responsible for 20% of all UK business CO₂ emissions, which to offset at £50 per unit would amount to £616 million (€715.11mn). He posed a key question: 'When will we see this liability on balance sheets?'

Watkins also showed delegates pictures of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the giant American multinational investment management corporation, and Mark Carney, an economist and banker who served as the Governor of the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020, to illustrate how the huge sustainability focus of leading major investment bank and finance figures like them had propelled it to the forefront of world commerce.

"Over the past few months, I have spoken to a load of chief executives and CFOs [chief financial officers] from companies all round this [UK building materials] sector who are being pressured beyond belief to make monumental differences to their businesses, particularly around circularity and carbon," said Watkins. "Investors are now saying, 'I know it's been like that forever, but unless you do something on sustainability, we are going to take our money and put it somewhere else'. Especially if you are a CRH which BlackRock already has an around 10% stake in, you are going to start listening to these people."

Watkins said he had been speaking to management at Forterra, a £380mn annual-revenue-generating concrete building block and brick manufacturing company based in Northampton, England, who told him that the firm's CEO, Stephen Harrison, spends 50% of his time dealing with sustainability investors. "That would not have happened five years ago," said Watkins, adding: "Forterra's CFO now writes the company's annual sustainability report."

Back to our conversation, Watkins says the UK building materials industry's sustainability focus went up shortly before, during and after COP26 [Glasgow, 31 October-13 November 2021]. COP26 was the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the third meeting of the parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement (designated CMA1, CMA2, CMA3), and the 16th meeting of the parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP16).

"Just look at how many businesses and organisations came out with net zero commitments in and around COP26. When you are talking about investors and investment instruments, there is huge pressure to decarbonise and drive up [production] circularity. Money has become conditional on making things better.

"As new generations come into industries, they are coming pre-programmed with a higher level of expectation of what businesses should be doing socially and environmentally. An enormous number of [UK building materials industry] people are going to retire, and a massive load of historic thinking will fall away. It doesn't mean that they were bad people and didn't care, but the younger people coming in are better equipped to handle sustainability challenges, given it is embedded in university courses, it is talked about at school, and there is more general discourse on the topic among twenty-something friends."

Watkins notes that several major building materials multinationals are in the process of selling parts of their traditional building products businesses to invest in new circular economy-linked product lines.

"Just look at Holcim selling off its India assets, with a third of the group's business planned to be not in cement but circular economy-based products. I think in the next five years, we are going to see a lot of larger building materials producers buying recycling businesses. Some of this is linked to skills acquisition. There is an awful lot more to do, but anyone putting money and time into more carbon reduction and circular economy-linked product production should be congratulated.

"If you look at asphalt, at the process level, everyone is desperate to lower the [production] heat and carbon, which is great. However, you need to take a step back and look at what that does to the binders and their embodied carbon. I read that Shell is investing in trying to harvest oils from plastics. There is a lot going on in this space. It requires a lot of people to work together and for people's expectations of products to change. If you are going to need carbon-intensive products, they need to be used wisely. Clearly, everyone wants high-quality concrete when building nuclear plants and bridges, for example, but there are other works that you may not necessarily need that product.

"Ultimately, you can become net zero by writing really big cheques and using credible offsets because any business will get to the stage where a little or a lot of offsets will need to be bought [to hit net zero targets]. The offsetting market is wholly unregulated. I think in the future, there will be a whole lot of new certifications and standards brought to it as the need for offsetting grows. I do worry about how quickly good quality offsets can be generated to meet demand. There is also, obviously, a cost issue around offsetting. I tell client companies that they need to work incredibly hard to get as much carbon out of their businesses as possible, so their exposure to the offsetting market is minimised."

I ask Watkins if there are any recently introduced building materials products that have caught his eye for their low carbon, circular economy-linked credentials? "I'm interested in Grosvenor Estate's 'steel neutral' buildings, where they harvest steel from one building and stick it in another. They are doing it because they can and are very interested in materials' circularity. This sort of thinking will become more prevalent – partly due to the intellectual challenge of it but also because it is a different economic model where companies own much of what they need going forward.

"A classic example of this is local authorities and their highways works. A lot of the stone used to make roads remains of similar quality to when it was first put down, and the local authorities could be asking, 'How much of it could be dug up and reused elsewhere?' You look at Hampshire County Council and OCL Regeneration [who are recycling material generated by road repairs and reusing it in road maintenance, reducing carbon emissions, costs, and travel miles]."

Does Watkins admire any mainland Europe countries for their work on building materials sustainability? "I think the Low Countries [Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg] have always been a set of nations further ahead on recycling, but a lot of that is for obvious reasons as they are countries with limited natural building materials, in particular hard rock. They do a lot of below-sea-level work and are further down the road as far as low-energy buildings are concerned. Germany is further ahead in terms of its green building standards and has been for a really long time.

"What I am definitely seeing in mainland Europe and in the UK is that the control of company sustainability programmes has become a lot tighter from wherever the centre is. In the aggregates industry, for instance, the sustainability content available to you from Aggregate Industries is from Holcim, and not so much locally driven."

I am curious to know what Watkins thinks about building materials major HeidelbergCement and its Italian subsidiary Italcementi's work on the 3D printing of construction materials, including its supply of concrete material to PERI who used a 3D COBOD concrete printer to create Germany's first printed residential building made of concrete in Beckum, North Rhine-Westphalia in 2020.

"Historically, and certainly with cement businesses, every time they came across something they found mildly threatening, they would buy it and lock it up, never to be seen again. Now there is licence to say, 'Yes, we must do something to protect our business.' This has resulted in loads of money turning up, whether via CEMEX's construction start-up investment vehicle, CEMEX Ventures, Holcim, another cement major or a sovereign wealth fund, which is being used invest in new technologies. 3D printed concrete is in that innovation sphere. No one technology will solve every building problem. We must try a bunch of stuff to see what works.

"I used to have a whole load of stats on the building materials industry R&D spending, and it was so far behind the tobacco industry it was staggering. As we go along the sustainability journey, this is changing as companies need to reshape their business models."

In a recent interview with Aggregates Business, Mineral Products Association (MPA) CEO Nigel Jackson described the UK mineral products industry's record on biodiversity as a "cracking success story" that the industry "needs to tell even more clearly than ever". He said the industry had created priority habitat already the equivalent in size to Nottingham, and a further area the size of Liverpool is already planned and in the pipeline. Despite this, Jackson said he had been disappointed by the lack of interest shown in this by DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs).

What does Watkins think of Jackson's comments? "I think there's been some monumental work done on biodiversity. It's been brilliant. I worry that there's too much emphasis on after rather than during minerals [production]. I am not as worried about the lack of DEFRA response. Sometimes, not being in the spotlight isn't a bad thing. We know what we are doing and where we are."

Watkins is concerned about unintended consequences surrounding efforts to secure 'biodiversity net gain', a compensation principle that applies to circumstances where a person or company, such as building materials firm, proposes to develop land, but where whatever it does results in potential biodiversity reduction. "There is a worry that if you are a building materials supplier with a planning application coming up, you will stop doing any conservation work as you may make it hard for yourself to do any biodiversity net gain.

Ultimately, you will need to deal with county council ecologists and say, 'Look, we've got a massive ongoing ecological programme here. Do you really want us to stop doing it?' It will then be up to them to decide.

"CEMEX has had a longstanding relationship with RSPB {Royal Society for the Protection of Birds}, and Aggregate Industries, in my time there and now, has worked closely with The Wildlife Trust. Biodiversity has been an amazing segue for the building materials supply industry to the public and third sector organisations. I think we can keep going on this and help other sectors, like housing – which is subject to the 10% biodiversity net gain principle."

Given Watkins' past sustainability-focused work at Aggregate Industries, is there a part of him that is envious of the great resources major building materials companies are putting into that area of their businesses? "I used to quite enjoy it in my time at AI; I quite liked the fight to get what I wanted and needed, the arguments and being the 'odd one out'. Saying that I am probably having more fun now working as an independent consultant rather than being part of a big business. I am lucky to be doing lots of interesting things for myself."

After 26 years working on sustainability issues within the UK building materials market, what is Watkins most proud of, and what is he still keen want to achieve? "I am most proud of what I did at Aggregate Industries. We were the first in the sector to do ISO14001 at scale, the first to do responsible sourcing, and we also won the London 2012 [Queen Elizabeth] Olympic Park aggregates and concrete supply contract. All of that was to do with our capability around sustainability and understanding of building materials life cycle assessment.

"Going forward, it is about getting our businesses going, Blue Planet Systems and my other business around polymers and waste plastic products. If I manage to do that, I will be very pleased indeed."