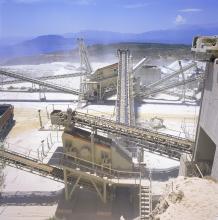

Italy is working to try and overcome a legacy of fragmentation in its aggregates industry to find a more efficient future. Adrian Greeman reports

Like many of the European countries Italy's aggregates industry began on a localised basis with many small firms and local demand satisfied by small quarries and gravel pits. As in many countries the industry has continued this way in the decades since the end of the Second World War.

But unlike most of the other countries in Europe, there has been little tendency to consolidate the production in this Mediterranean peninsula. Production yards and stone extraction pits are small and family owned to this day and the major global conglomerates do not have the same control as they do in other European countries.

Even compared to Germany, which also has a high proportion of small family businesses, Italy has an extraordinarily high level of small production, said Francesco Castagna, general secretary for the

"There are 1900 companies in the aggregates business in Italy and they operate 2500 quarries or extraction pits. That is only an average of 1.5 quarries to a company," he said. "Most of these are small or medium sized businesses employing up to five people and the largest usually no more than ten.

"Bigger companies which have consolidated the industry in countries like the UK especially, and France, the Netherlands and elsewhere, are almost unrepresented in Italy.

"The presence of large companies, primarily in the cement sector and ready mix buying aggregates for their own production, is very limited and accounts for no more than 2% to 3% of the sector."

Geology and geography

Various factors seem to have contributed to the shape of the industry from geography and geology to the historical, economic and political development of the country.

Perhaps one factor is the lack of large waterways in a Mediterranean climate which rules out water transport for moving aggregates. Railways too are rarely used for transport; where they run, there are usually local supplies and further south, where supplies might be moved further, there is less demand.

Road transport is the norm therefore, reinforcing the distance limitation on supply which always affects the aggregates market and its bulky products. As with most countries, the heavy gravel and sand rapidly rises in cost as fuel expenses are added to move it and a maximum range of around 50km is normal for supplying the product.

This combines with geography - Italy effectively splits into two great areas, the huge flat plain of the Po valley in the north, formed by the great wash of erosion products from the rising Alp mountains on the northern border, and the mountain chain that forms the spine of the country southwards and into Sicily.

Rock is highly variable from the famous hard marbles of the Carrera district north of Florence to sedimentary and mixed rocks throughout the chains. Famously too, Italy has its recent volcanic deposits around still live volcanoes like Etna, Stromboli and Vesuvius. The earliest concrete, used by the Romans, came from mixing the pozzolanic ash deposits around Naples with aggregates; a lightweight concrete with pumice formed the dome of the 2000 year old Pantheon in Rome.

In the south, all this means quarrying and crushed rock products are more used than other types of deposits. In the north, a profusion of gravel deposition on the plains means almost all the supply is from natural gravel and sand.

"There are a large number of rivers running south from the Alps and limestone-formed Dolomite mountains further east bring eroded rock into the plains," said Castagna. Typically the coarser stone and large gravel tends to be found northwards and finer product gets washed further south.

In the past these deposits were often exploited directly from the river beds but because of environmental, and possibly deleterious hydrological impacts, this has now been banned except if there are civil works needed on a river course for other reasons. "In this case the aggregates which have to be dredged or excavated are allowed to go into the local supply," said Castagna.

Large numbers of gravel pits have been worked however. The northern area of Italy has tended to be the focus for industrial, and much of the general economic, development, and many of the big plains cities from Bologna, to Milan and Turin, and the whole Venetian hinterland have grown substantially over the last 100 years.

Short focus

The relatively easy access to gravel in the plains area may have been one reason for the short term emphasis on aggregates supplies with deposits sometimes worked for just two or three years and less longer term extraction. The longer term nature of hill quarrying has been in the less economically favoured south.

Short term production is also a consequence of Italian law which is a complex and varied mix of provincial and regional regulation that varies substantially from district to district.

It results partly from the relatively recent national unity of Italy, and the continuing regional fragmentation of much administration. It finds expression in many industries, with the small workshop a feature of the country's continuing economic development alongside the bigger factories of

When it comes to licensing there is a multitude of small and lower level administrations to negotiate, most particularly the municipality which has many of the powers for granting licences. A city may be very large like Milan with more than one million inhabitants but it can also be very small and local, sometimes with a population as low as 50 inhabitants. "Not even enough for a full time mayor," according to the recently elected president of ANEPLA Cirino Mendola.

There are over 8000 such municipalities which take decisions. Above them are the 21 main regions with licensing powers and sometimes the provinces within them have powers delegated to them too. But the smaller bodies have to be negotiated with as well. "Each of these provinces makes its own rules," said Mendola.

On top of that is the problem of time limits. Most licences to extract are only for two or three years and must be renegotiated after that period. "It hampers the modern management techniques of larger companies which with a long term perspective can tailor investments and equipment to give better returns, and which are able to take better coordinated measures on restitution and re-instatement," said Castagna.

ANEPLA has been battling for many years to win national level legislation to change this situation.

It has succeeded in recent years in establishing the aggregates sector as a mainstream industry alongside other industries it believes, and no longer as a small scale transient phenomenon. With it has come more acceptance that the industry can contribute to landscaping and amenity works as part of its operations, and that a wholly negative view of its impact is misplaced.

A variety of parkland schemes and amenity works on gravel pits in the Po plain have helped begin shifting the view of populations towards the industry and it is more possible than in the past to negotiate arrangements with local authorities for the restitution of works and future amenity use.

"People who have had pits in their area before, they can understand that the activity is OK and not affecting life exceptionally, and that later it will bring benefits in the form of a beautiful lake or something like that," said Mendola.

But there is a way to go to achieve standardised and longer term licensing practice. That exists in the mining sector which has a national legal framework for approvals and licences. But for the aggregates sector at present it remains "a dream", according to Mendola.

He would like to see national regulation developed for the industry as it has been for the mining sector, both historically and in the years of increasing regulation by the

"We need a specific national law with uniform criteria for the production planning on a national level and standardised technical regulation of exploitation." The industry would also like a more rigorous and precise definition of the rules governing sources of production,

by which he is referring to what is required in restoration, landscaping, environmental standards and the like.

That also includes that aggregate sources should be a criteria in all general planning with surveys of where the best of them are located and their possible future use to be considered in all planning activities.

A confusing issue for the industry is constantly changing regulation on how unpolluted or non-toxic ground waste material from construction and other activities should be treated.

"For example issues around land improvement in agriculture where aggregates are removed, the treatment of recovery material from quarries used in bigger public works and the treatment of construction demolition and waste," said Mendola.

Other issues that need attention include recycling and health & safety, he says. Recycling is not extensively practised in Italy, possibly for the reasons above and developing much greater use is a priority for the industry.

Castagna, like many others in the industry, points to the importance and universal use of aggregates in everything from building and construction, particularly for roads, to industrial products which use aggregates in their manufacture. He explained, "Everyone understands that you need aggregates but it is always a 'not-in-my-back-yard' understanding." He hopes that view might be changing a little.