Researchers are developing a method for using bacteria to develop building materials that live and multiply.

A team at the University of Colorado Boulder in the US says the strategy might also deliver materials with a lower carbon footprint.

“We already use biological materials in our buildings, like wood, but those materials are no longer alive,” said team member Wil Srubar, an assistant professor in the university's Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering (CEAE). “We’re asking: Why can’t we keep them alive and have that biology do something beneficial, too?”

The research is still at the development stage, but the team say that their ability to keep their bacteria alive with a high success rate shows that living buildings might not be too far off in the future.

They claim that such structures could one day heal their own cracks, suck up dangerous toxins from the air or even glow on command.

“Though this technology is at its beginning, looking forward, living building materials could be used to improve the efficiency and sustainability of building material production and could allow materials to sense and interact with their environment," said study lead author Chelsea Heveran, a former postdoctoral research assistant at CU Boulder, now at Montana State University.

They add that current "more corpse-like" buildings materials, in contrast, can be costly and polluting to produce. Srubar said: "Making the cement and concrete alone needed for roads, bridges, skyscrapers and other structures generates nearly 6% of the world’s annual emissions of carbon dioxide."

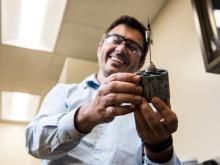

Srubar and his colleagues experimented with cyanobacteria belonging to the genus Synechococcus. Under the right conditions, they said that these green microbes absorb carbon dioxide gas to help them grow and make calcium carbonate — the main ingredient in limestone and cement.

To begin the manufacturing process, the researchers inoculate colonies of cyanobacteria into a solution of sand and gelatin. With the right tweaks, they said the calcium carbonate churned out by the microbes mineralises the gelatin which binds together the sand and produces a brick.

In addition, the researchers say such bricks would actually remove carbon dioxide from the air, not pump it back out.

In the new study, the team discovered that under a range of humidity conditions, they have about the same strength as the mortar used by contractors today. “You can step on it, and it won’t break,” said Subar

They also found that they could make their materials reproduce. Chop one of these bricks in half, and each of half is capable of growing into a new brick.

The new bricks are claimed to be very resilient. According to the group’s calculations, roughly 9-14% of the bacterial colonies in their materials were still alive after 30 days and three different generations in brick form. Bacteria added to concrete to develop self-healing materials, in contrast, tend to have survival rates of less than 1%.

“We know that bacteria grow at an exponential rate,” Srubar said. “That’s different than how we, say, 3D-print a block or cast a brick. If we can grow our materials biologically, then we can manufacture at an exponential scale.”

While there is much work still to do, Srubar maintains that the possibilities are big. He imagines a future in which suppliers could mail out sacks filled with the desiccated ingredients for making living building materials. Just by adding water, people on-site could begin to grow and shape their own microbial homes.

This article first appeared on our sister title Aggregates Business.