Dutch researchers have produced tablets that help concrete repair itself

A self-healing concrete that can patch up cracks by itself is being tested outdoors, say researchers at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) in the Netherlands.

The experimental concrete contains limestone-producing bacteria that are activated by corrosive rainwater working its way into the structure.

Developed by microbiologist Dr Henk Jonkers and concrete technologist Professor Eric Schlangen, the material could potentially increase the service life of the concrete with considerable cost savings as a result.

“Micro-cracks are an expected part of the hardening process and do not directly cause strength loss, but in time water can seep into the cracks and corrode the concrete,” they said.

“For durability reasons (in order to improve the service life of the construction) it is important to get these micro-cracks healed,” said Dr Jonkers, when speaking to BBC News.

Bacterial spores and the nutrients they will need to feed on are added as granules into the concrete mix, the researchers said, but the spores remain dormant until rainwater works its way into the cracks and activates them: they then feed on the nutrients to produce limestone.

The Self-Healing Materials Programme at Delft Centre for Materials was established in 2004 with a central research theme of the development of self-healing materials. At the time it involved a consortium of 22 TU Delft research groups.

Buildings and structures made of concrete are exposed to the elements for years, even centuries, and air, changes in temperature and especially moisture can weaken even the sturdiest of materials over time.

The new generation of materials that can repair themselves is less expensive than putting up a new building, and better for the environment.

The inspiration for self-healing concrete comes from nature: limestone-producing bacteria.

When embedded in concrete, these bacteria should be able to repair cracks in it. However, to be able to survive in the concrete, they have to come from good stock: the pH-value of concrete is around 13, which is an extremely alkaline environment.

The bacteria also have to be able to survive the concrete mixer and then they have to wait for years before being able to carry out their restoration work.

Bacteria of the bacillus species have exactly the right characteristics.

Their spores can survive for decades in a kind of sleep mode, without food or oxygen.

In concrete, they will only come to life if water and oxygen are added (if a crack appears in the concrete).

They are then able to multiply and produce limestone, thereby closing the crack in a few weeks. Once the crack is closed up completely, moisture can no longer get into the concrete, so it will not weaken.

This is seen as the perfect solution for underground spaces, for example, in which it is always damp.

A healing agent for concrete has been developed that is made up of two components: bacillus spores and calcium lactate nutrients.

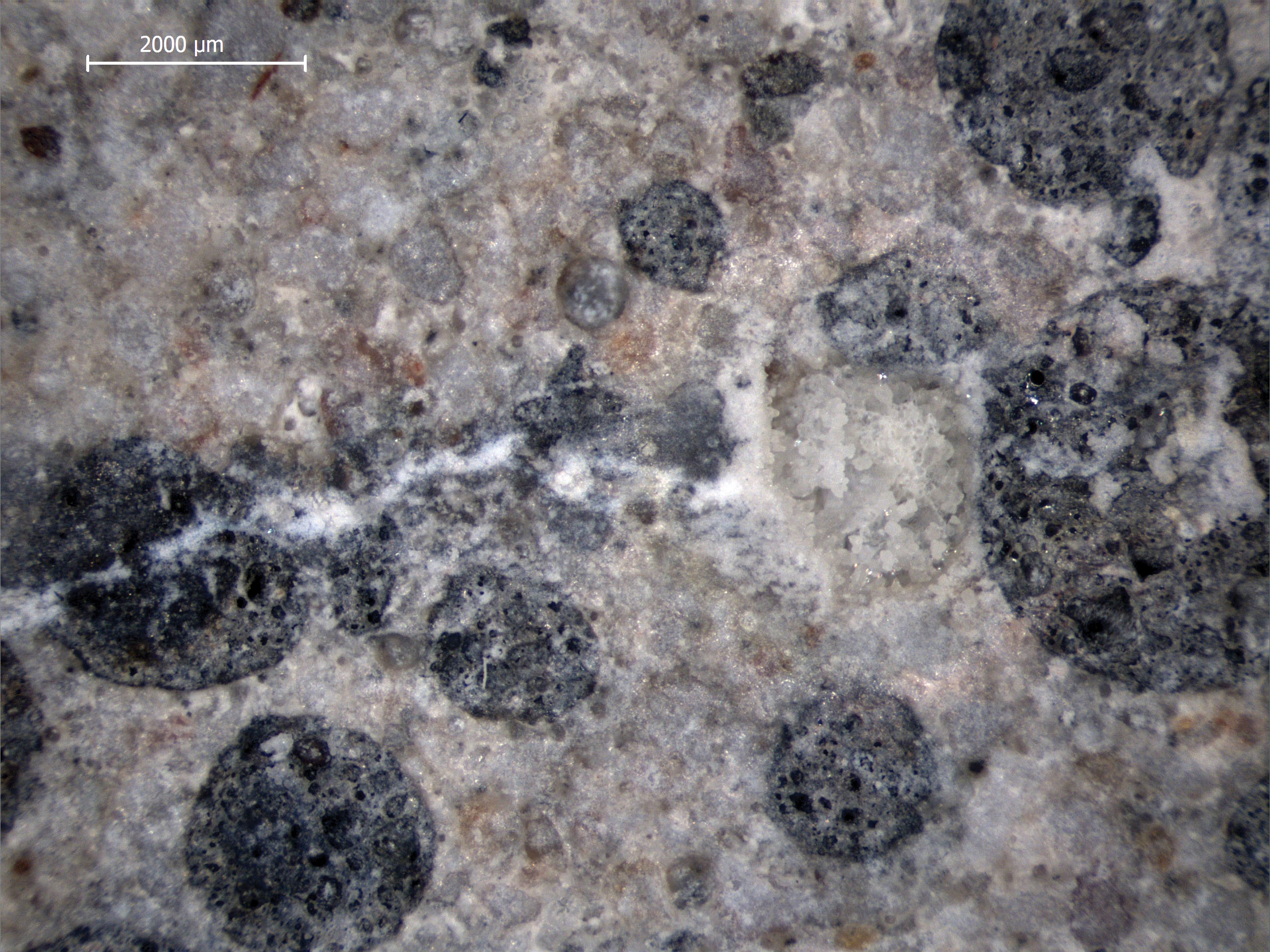

These are set separately into expanded clay pellets, or alternatively in compressed powder granules, a few millimetres in size. The pellets are then added to the wet concrete mix.

When, hopefully years later, cracks begin to form in the concrete, water will enter and open up the pellets.

The bacteria will germinate and start to feed on the lactate, thus combining the calcium with produced carbonate ions to form calcite (or limestone).

Full scale outdoor testing is under way. A building in the south of Holland has been covered with the bio-concrete and will be monitored over a period of two years.

For Dr Jonkers, winning the Delft Innovation Award 2009 was of crucial importance because it helped with funding to continue his work.

Already he had shown that his self-healing concrete proved to work in a laboratory but with the valorisation bonus that came with the award he was able to put his invention on the market.

Last year Dr Jonkers, interviewed for TU Delft, said: “Winning the Delft Innovation Award and the valorisation bonus made it possible to take the first important steps out of the lab towards the market.”

He invested the bonus in finding ways to produce bio-concrete on a larger scale, and spent a part of the money buying chemicals and several devices to turn the bacteria into tablets.

“It is a challenge to make small tablets that could easily be mixed with the concrete.

“The market will only adopt the product if it is cost efficient. Therefore I have to make sure the tablets are as cheap as the concrete.”