Belgium is trying to answer a very big question: How do you balance a nation’s significant construction industry need for high-quality sea sand with limited marine space?

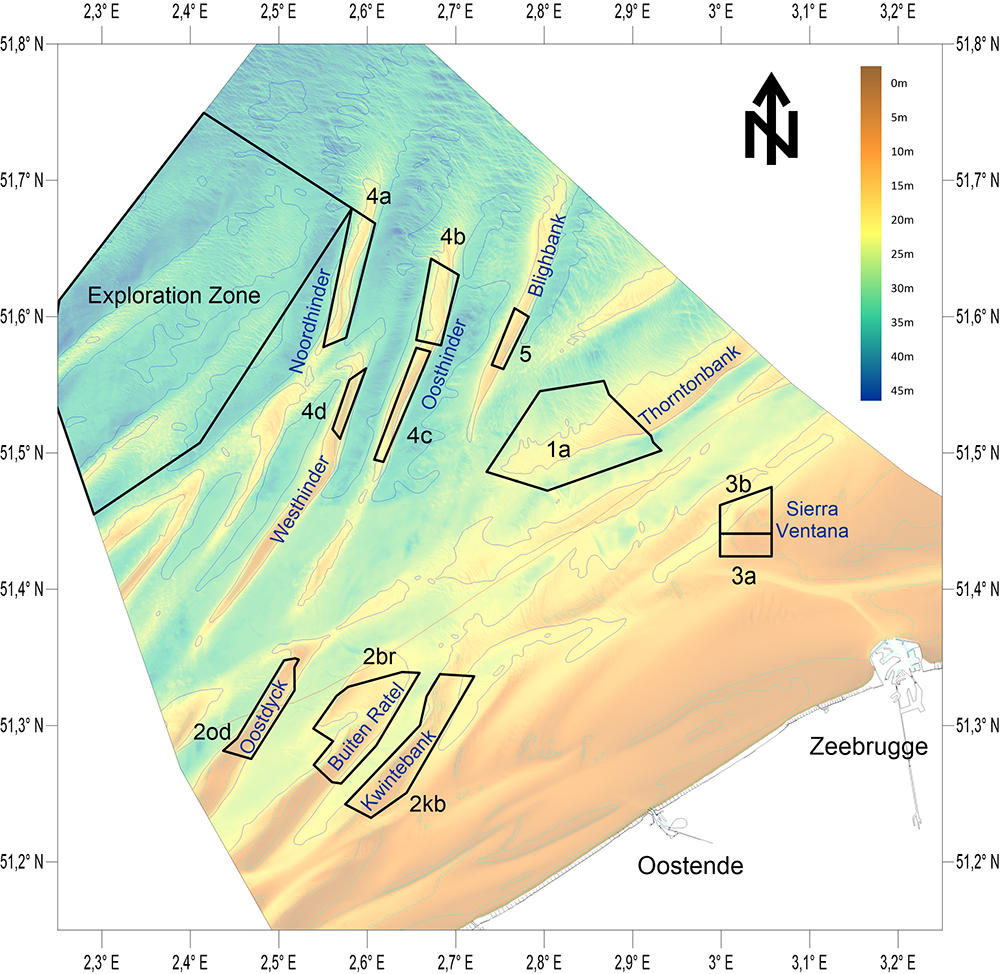

Each year up to 3 million m³ (4.5mn tonnes) of sea sand can be extracted from up to 11 permitted extraction sites (not all currently used) along Belgium’s 3,600km² North Sea coastline. New regulations on sand extraction which came into practice on 1 January 2021 to protect the sea floor and reduce the prospect of geological damage mean that each extraction site has a specific dredging depth depending on the damage risk. The change from what had been a blanket up to 5m-dredging depth rule followed extensive research by the Continental Shelf Service (COPCO) of FPS Economy (Federal Public Service Economy), an administration of the Belgian federal state that focuses on the economy and registering sand extraction in the Belgian North Sea, in collaboration with the Royal Belgian Institute of National Sciences and the Institute for Agricultural, Fisheries & Food Research.

There has been a big debate in Belgium on whether to raise, maintain or lower the current 3 million m³ annual sea sand extraction limit. While the country’s industrial/construction sectors and those responsible for coastal safety infrastructure and beach sand replenishment are in constant need of large quantities of premium sea sand, the Belgian government is keen to erect more wind turbines in the Belgian North Sea as part of its increased commitment to renewable energy supply.

One prominent sea sand extraction site was partially closed in 2004 to make way for an offshore wind park, with another extraction site also due to be shut soon to accommodate another wind turbine site.

Certain sea sand extraction sites also fall under the auspices of Natura 2000 - a network of nature protection areas in the European Union made up of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas designated under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive, respectively. The network includes both terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas. This has led to a reduction in sea sand dredging at three extraction sites within ‘Control Zone 2 – Flemish Banks’. The reduction in this type of extraction also complies with the Belgian Marine Spatial Plan 2020-2026.

The Belgian Marine Spatial Plan (2020-2026) permits the identification and use of new sea sand extraction sites, with FPS Economy’s COPCO and its partners playing a leading role in this area. They have identified a new area, thought to be the last untapped area of the Belgian Continental Shelf, for potential sea sand extraction and are currently in talks with relevant Belgian government authorities on its viability.

The future of sea sand extraction in the Belgian North Sea was the key topic of FPS Economy’s recent sand extraction study day under the heading A 360° Perspective on Sea Sand held at Zwin Natuur Park in Knokke-Heist, on the Belgian-Dutch border. The event was attended by more than 100 senior figures from the marine aggregates industry, national and regional government, academia, and environmental protection agencies.

Attended by Aggregates Business, the sea sand study day highlighted how FPS Economy’s monitoring and registering of sea sand extraction will soon be entirely digitalised, allowing for easier data sharing and use of GIS (geographic information systems) software to explain and showcase findings. Florian Barette, FPS Economy’s sand extraction analyst, highlighted the ability of the Continental Shelf Service to monitor the Belgian North Sea sand extraction sites in near real time based on AIS (automatic identification system) data.

Talking to sea sand study day attendees, Aggregates Business picked up concerns that politicians’ keenness to ‘be seen to be green’ by investing in renewable energy supply, a perceived public vote winner, was not helping with the process of communicating the importance of a thriving sea sand extraction industry to Belgium’s vital infrastructure development.

One of many detailed presentations during the study day came from Tom Janssens, general manager of DEME Building Materials and a senior figure in ZEEGRA, the Belgian association of importers and producers of dredged marine aggregates. Janssens highlighted that the association had 10 member companies licensed to dredge sea sand on the Belgian Continental Shelf (BCS). The active fleet consists of 15 dredgers with an average hopper volume between 2,000 and 3,000m³.

Janssens explained that to qualify as a suitable sand source for the construction industry, there are several key requirements to be met in terms of quality, quantity and cost. The quality of the sand has to be good/sufficient and constant. The main quality parameters are grain size distribution, the absence of organics, low shell content and colour. Sufficient volumes have to be available now and in the future. As in any economic activity, cost is an important aspect. Key factors that affect cost are sailing distances, dredging depth and the ability for in-line separation of oversize (+8mm) material.

“Over the past 50 years, the use of Belgian marine sand in construction has gradually increased, thanks it its own merit – good and very constant quality, as a welcome substitute for diminishing on-shore resources,” said Janssens. “The legally imposed level of 3 million m³ per year is now reached. Whether or not to increase this level is a political choice, whereby the balance is considered between current and future availability. Although sand can be extracted in a sustainable way, it is a non-renewable resource.

“From the perspective of sustainability, the introduction in 2021 of the new reference surface as the bottom limit for extraction is a major step forward.”

Janssens said the increased activity in the Belgian North Sea, especially the increase of green energy infrastructure, and the installation of additional cables and pipelines, has meant that “very large volumes” of good quality construction sand have been temporarily blocked from immediate access.

“This is no problem in the short term, but over the long term this definitely has to be a point of attention in marine spatial planning. Good-quality construction sand is a vital and non-renewable resource. The extensive studies leading up to the new reference surface have confirmed the availability of very large sand resources outside the currently active control zones. These resources have to be safeguarded as a future reserve.

“Appropriate legislation is required on the design and installation of offshore infrastructure [cables and pipelines], to enable the complete removal of all obstacles from the seabed at the end of their economic lifetime. This will enable future spatial planning to make these reserves available again for sand extraction, whilst the control zones that by then will be extracted down to the defined reference surface, can then be made available for other seabed users. This long-term dynamic interaction will have to be introduced more and more in the future spatial planning to safeguard and optimally use the scarce but very good quality sea sand reserves that Belgium possesses on its Continental Shelf.”

Representing UEPG (European Aggregates Association), Ingo Hammwöhner noted that large quantities of building materials such as gravel and sand are needed to adapt to the impacts of climate change. “The marine aggregates industry can play a crucial role in implementing necessary coastal protection measures and coastal infrastructure projects, as well as in the construction of renewable energy plants and environmentally friendly, energy-efficient buildings. Especially in coastal regions where local, land-based sand and gravel deposits are increasingly scarce or non-existent, marine deposits play an important role in the supply of raw materials. For certain coastal measures and projects, they are without alternative.”

Jeroen Vrijders, of the Belgian Building Research Institute (BBRI), highlighted how the construction sector uses sand in many applications including concrete, mortar, building blocks, glass, and foundation layers. He explained how a distinction is made between ‘fine’ sand or filling sand, used in landscaping, and ‘coarse’ sand, coming from rivers, the sea, sand pits and manufacturing processes in quarries.

“Currently, the excavation of sand worldwide is twice as big as the natural production – 40 vs 20 billion tonnes. Many technological developments are ongoing to address the potential scarcity of construction sand in the future. Concepts like the circular economy and the trias materialis can help in the future to use sand efficiently and integrate alternatives in practice.”

Elias Van Quickelborne, of the Agency for Maritime & Coastal Services, Coastal Division, which falls under the Flemish Ministry of Mobility and Public Works, said that since 2011, 13.2 million m³ of sand had been deposited on Belgian beaches in the interest of coastal safety. “About 84% of this comes from the primary licensed extraction zones on the Belgian Continental Shelf. The remaining 16% falls under the term ‘beneficial use’. Sandy dredged material or sand from small to large (infrastructure) works on- and offshore, finds a useful application in sea defences if all quality requirements can be met. The intention is to at least increase this share in the coming years and to actively look for new synergies around. Therefore, the demand for primary sea sand can be significantly reduced, aiming to make a positive contribution to the circular use of raw materials and reducing the cost of the nourishment programme.”

Van Quickelborne stressed that it is always better to retain sand in places where it is of maximum use. He continued: “Successful projects involving the planting of marram grass and the fixation of sea defense dunes are in full development in Westende, Raversijde, Mariakerke and Oostende Oosteroever in collaboration with various scientific institutions.

“At the beginning of October 2021, construction began on four new beach groynes [low walls] in the critical and maintenance-intensive area around Wenduine. The purpose of this proven technique is also to retain the sand and to reduce longitudinal transport to the marina of Blankenberge.”

Van Quickelborne said special attention should also be paid to the final part of the Flemish coastal safety masterplan, adjacent to the Dutch border. “In the 2016-2019 period, sand from deepening the main channel at the Zwin entrance was used for the construction of the core of a new 4km International Zwin Dike. Large-scale works that led to the rebirth of the Zwin nature reserve.”