Renewable energy has become an attractive option for extractive industries wanting to offset increasing energy costs. UK renewables lawyer Sonya Bedford explains

There is increasing evidence that extractive industries are turning to renewable energy to offset their own energy consumption and use landbanks for the development of renewable energy capacity and income generation.

Recent examples include

Elsewhere in the UK, industrial minerals giant

Similarly,

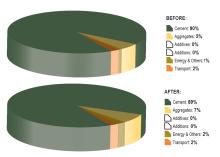

In Turkey, joint venture cement company Akçansa is planning to tap redundant heat from its clinker operations to produce high-pressure steam to turn a 15MW turbine. This will slash the energy costs of one of its plants by a massive 30%.

Mining and minerals sites can also be suitable for wind energy projects, an example being the Lisheen Mine in Ireland where 18 turbines generate 36MW of electricity.

All of these examples are driven by a combination of commercial and environmental considerations, against a legal imperative on member states to reduce carbon emissions and generate 20% of their energy from renewable resources by 2020, or face penalties.

Incentives

This in turn has spawned a system of feed in tariffs (FIT) across 22 member states and incentivised payments or tax exemptions in others, all of which are geared to promote the uptake of renewables by industry and contribute to hitting the 2020 target.

FITs are a popular way of incentivising renewables by paying a fixed rate of return on renewable electricity generated, usually over a long period of between 10 and 25 years. But some member states have already scaled back their FIT commitments for solar in particular, fearful that the market was overheating.

Last year Germany adjusted its solar FIT structure, reducing payments in several areas and shifting the photovoltaic (PV) focus to rooftop installations. Field scale installations of PV - of the type being proposed by many aggregates operators - were taken out of the FITs system.

Spain has also been cutting back on its PV incentives since 2008, and 2009 saw a sharp drop-off in activity as solar investors took flight in the face of falling returns.

The same thing has been happening in the UK where a Government review of FITs for field-scale solar schemes will see subsidies slashed by around 70% from 1 August this year. Legal action against reductions in FITs is pending in a number of member states.

But despite these cuts in subsidy there is no doubt that solar will make a significant contribution to meeting the EU's 2020 renewables target, and as volume production of PV increases, fuelled by member states' intervention through the use of tariffs, so the cost will reduce and become more viable without the need for hefty state subsidies.

Ground mounted solar panels are attractive to the extractive industries because they can be relatively easily installed on long worked-out sites, from which the company can derive a direct financial benefit while contributing to carbon reduction. Many of these sites are also suitable for wind energy and without the planning issues that can accompany developments in more built up areas.

Planning

For any business investigating renewable energy as a potential source of income or reduced energy costs, it pays to do your homework. Under an EU directive from 2009 grid operators are supposed to give renewables projects full access to the grid but it can vary from state to state and there are often complaints about punitive connection charges and lack of transparency.

Red tape is another issue that can vary widely between member states. While the Germans are largely seen as having got it right, research for the European Commission suggests that securing the necessary permits for a renewable energy installation requires the permission of nine different authorities.

There is no doubt that renewables will become an increasingly important part of the EU's energy mix, and the land banks that exist within the renewables industry means it is well placed to take advantage of the green energy revolution.