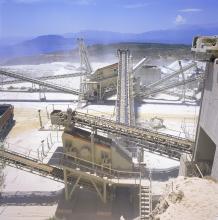

Staggering growth in the Spanish aggregates industry has curtailed recently due to the housing market fall-off. Adrian Greeman reports

Spain has seen a booming market for the aggregate industry in the last fifteen years, witnessing an astonishing rise in production. Demand for quarried materials more than doubled between 1992 and the end of 2006. According to figures from the National Association of Spanish Aggregates producers (

In 2006 it produced 485million tonnes of sand, gravel and crushed rock for the construction industry, with another 75million tonnes for industrial use. Sales for 2006 were just under €4billion for the construction and transport sectors alone.

These figures place Spain second only in output to Europe's biggest economy in Germany, which is especially significant considering the country has a population of 40million - just under half of Germany's 82million.

"That works out at 1.2tonnes per person compared to say France where it is 400kg per person," said ANEFA general secretary César Luaces Frades.

However, this titanic growth may be faltering and both the association and bigger international firms like

Like elsewhere, Spain has been feeling the impact of the subprime mortgage collapses in the US, and the worldwide credit crunch which has been a knock-on effect on construction.

In fact Spain may suffer more of an effect than most countries. One of the key factors driving demand in past years has been an extraordinarily high demand for housing and within that, an extraordinarily high proportion of overseas demand for properties, notably from Latin America and from tourism associated purchases. Alongside have been retail parks, golf courses and other tourism and retirement related private projects.

Tourism is a major industry and retirement housing too. "As much as 15% of national housing demand is from northern countries in Europe, in particular Germany, Finland, Scandinavia and the UK," said special projects director at Hanson Hispania, Carlos Sanchez. Within the tourist regions, largely the Mediterranean coasts like the Costa del Sol and Costa Blanca, this proportion is much higher, and they have been hit correspondingly hard.

The effect may be compounded by a tendency for the Spanish economy to be skewed towards housing anyway with a corresponding weakness in manufacturing and industrial development. According to a Financial Times article published last year, "construction and housing accounts for 18.5% of gross domestic product, about twice as high as the Eurozone average, according to data from the EU's Ameco database. The comparable figure for Germany is 8.7%." The effect has been for the housing boom to drive economic development with rising prices sustaining other activity, as it has in the UK, for example. With a fall back this economic engine turns much slower.

Infrastructure investment

Two other effects may compound the problems and both reflect the nature of the Spanish economy.

Spain developed very quickly in the 1990s, in part because it was bouncing up from decades of suppressed development during the Francoist period, whose traditional and conservative administration had not given free reign to investment and industrial developments. When Spain joined the

The European Union has also been good for Spain in a very direct way with significant development money pouring in from Brussels via infrastructure funds and the special "structural" development funds made available in the 1990s to even out the imbalances across Europe. Portugal, Greece, Ireland and Spain were the major beneficiaries of the latter.

Spain has carried out some very large infrastructure projects with major motorway building, and the creation of a network of high speed railway lines rivaling the 320km/hr TGV system which has been so successful in France. Earlier this year the remaining part of the 650km long Madrid-Barcelona line was opened - somewhat behind the original schedule but to great acclaim, and a variety of other lines radiating from Madrid, to cities like Toledo, Seville, Malaga and Vallalodid have been built with more due.

Some €16billion has been spent on high speed rail links so far said a spokesman from the Spanish Road Federation. Another track to link with Portugal's capital Lisbon is in development.

Madrid has been the scene of major road development with a pattern of city ring expressways. A third €4billion ring was recently added and a pattern of radial toll motorways has been built too.

A 900km long motorway from the south through the west central part of Spain and on into the north west is currently still in construction.

Madrid has also seen the major expansion of its Barajas airport with a giant terminal and two new runways, and significant expansion of its underground metro network as well, with several new lines including one out to the airport, and a huge amount of housing, commercial and retail development.

Port works are also being done at Barcelona, Valencia and Gijon.

But with European enlargement and the accession of much of Eastern Europe, Cyprus and Malta, the country now has to compete with many more demands on the infrastructure funds; much of the budget formerly available is now going elsewhere into countries with relatively undeveloped infrastructure.

Demand impact

There are still funds from Brussels and the government has money of its own to put into projects said Luaces, who believes there is a stepping up of major civil engineering taking place by government to keep the economy moving and compensate for the housing sector. "It is hard to predict the impact these changes will have though perhaps demand may fall back 10% or 20%. Even so, 80% of this high level of 500million tonnes is still high," he said.

The effects of the fallback might ease some difficulties the industry has been having however, in opening new reserves. It may also speed up consolidation of the industry.

"Spain's aggregate sector is fairly diverse and still with a wide spread of small companies operating, some with just two or three people," said Luaces, "Very often they are all family members."

Of the 1750 active companies in the association around 80% are of this scale.

This structure partly reflects the geography of Spain, he explained. The country is the second largest in area in Europe after France and with a sparse population in many areas, especially several large mountain ranges, like the Pyrenees and the Andalucian mountains, and the high central plateau. Rural depopulation has continued for decades.

Production from these small firms is only about 25% of the total however. Most of the remainder of the companies are medium size enterprises producing annually between 500,000tonnes and 2million tonnes of material. They still only produce another 50% output however. A dozen or so of the big players produce the remaining 25%, focusing largely on the high demand areas along the coast, and around major cities like Barcelona, Bilbao and Madrid.

Geology of the country covers just about everything, according to Luaces, with a varied mix of materials available in most of the regions. Even so around 56% of Spain's aggregates output is limestone. "There is also basalt, granite, dolomite, and so on," he said.

Crushed rock accounts for a larger proportion of the output than in many countries; some 70% of the supply is from rock quarries. "But there has been a preference for natural sand and gravel," said Luaces.

Spain has far fewer large rivers than the wetter north of Europe however, and many in the south are seasonal affecting where river bed deposits can be won, especially as water extraction demands can conflict in especially southern parts of the country.

For the same reason transport by water of aggregates in Spain is largely ruled out. "The rail network is not suitable for much heavy freight," said Luaces. "Delivery is 100% by truck." As with other quarries in Europe, that tends to mean a maximum radius of cost effective delivery of about 50km.

But finding quarries within range of development is a major problem, and in some areas such as Madrid it is almost impossible. "One company took seven years to get permission to extract," said Luaces.

Reserve issues

"Consumption is very high and that means obvious reserves are getting limited but winning permission for opening new quarries is extremely difficult in Spain. It is our number one problem at the present time." Hanson's Sanchez agrees that gaining permission is extremely difficult and added, "In Catalonia for example there has not been a new quarry opened for 20 years; expansion is all in existing quarries." Much of the problem lies in a two tier system of approvals needed to open quarries.

First a company must obtain permission from the central government's mining department and at regional level, as well as making an environmental impact statement to demonstrate its case is sound.

"But then you must get permission from the local mayor," said Sanchez. In many cases this can be almost impossible because no particular town or village wants to have a quarry nearby. Even Madrid has forbidden further extraction within its administrative region around the city, so that aggregate has to come from nearby regions.

Local decisions can be challenged and the association and some companies have taken cases to court, though of course this can be long winded.

The cases are not helped however by growing environmental restrictions in Spain which now has about 25% of its geography covered by protected zones and national parkland. "We have a significant biodiversity in the country which should rightly be protected," admitted Luaces.

Like anywhere the demands for restoration and reinstatement of works have grown as well. Companies must submit their ongoing landscaping and reinstatement plans as part of applications.

European rulings, and campaigns like Natura 2000, have added to the difficulties, and Spain tends to take these issues even more seriously perhaps because it is aware of the importance of tourism to the economy, which makes natural landscape of direct economic benefit.

"Of course this is an issue everyone faces," said Luaces. "But it is a particular problem here."

One impact has perhaps been on consolidation of the industry. The big companies have been keen to buy into the market, not least for the precise reason that high demand and limited supply can only help keep their sales buoyant.

But quarries have only appeared on the market at high prices because owners are conscious of their value. Purchases have been slow therefore.

That could change if demand for aggregate slows and prices now fall back somewhat. Quarry owners may be more ready to sell and perhaps the industry will see the larger companies spreading out further from the seven or eight quarries that most of them control at present.

That seems more likely than any major growth in recycling, for example. Because of its wide ranging geography the country has not developed the use of demolition material re-use, which tends to happen more in urban areas, if only because of the need to avoid long transport overheads.

"There is some, around 2.5million tonnes a year," said ANEFA. It could grow in future especially as the EU sets usability standards for the material, and may reach 4 to 5% of total use.